Cousin Koala

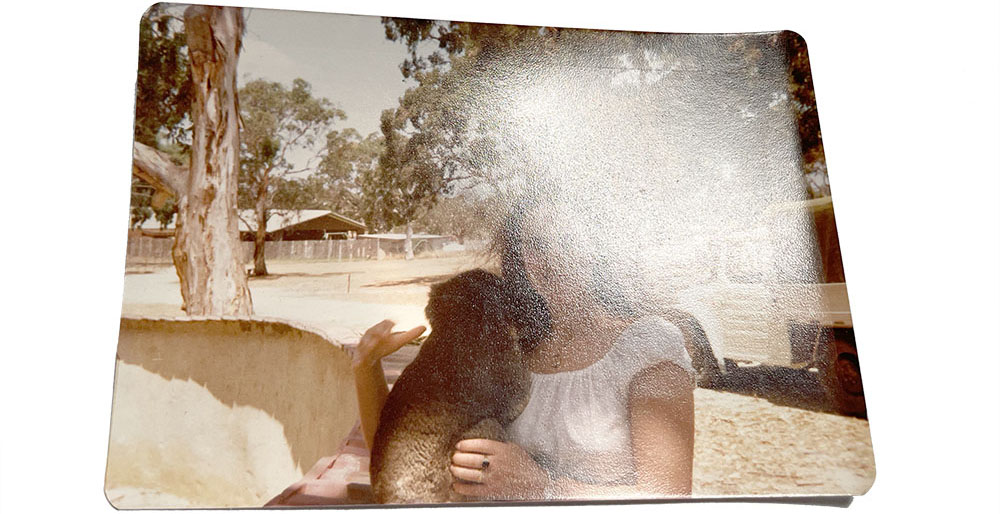

Greeting cards and photographs sent by my godmother from Australia filled my childhood like messages from another world. They drew me into the reveries of golden beaches, huge waves, red earth and crusty bushland. There were amazing cities with buildings like sailing ships. My godmother posed among an eclectic mix of companions – sometimes joined by other members of our human family, and in many others, surrounded by fantastic creatures unlike anything I knew – kangaroos at ease by her side or birds bigger than her. They all seemed equally familiar, yet strangers all the same.

Among them was one recurring theme – she was posing with a koala bear nestled in her arms. There was something maternal about her gesture, and, in my childhood imagination, this sleepy bear was her baby. This didn’t surprise me much as I didn’t have siblings, and since we lived far from anywhere, I hardly ever saw other kids or got a sense of how families were meant to be. So, to me, it made perfect sense that a koala was her child, thus, my cousin. Although a rather strange family member, after all, anything could be possible in such a beautiful and mysterious country.

To immigrate to Australia, my godmother took a path as extraordinary as the destination itself. Her success was impressive given the strict controls the communist regime in Poland placed on international travel, particularly beyond the Iron Curtain. She managed it through a correspondence marriage with a gentleman of English citizenship, a manoeuvre that enabled her to obtain a passport and permission to leave the country. With little savings from economically stagnant Poland, she could afford only a passage aboard a merchant vessel, and her journey stretched over three months. Once settled in Australia, she went on to facilitate the immigration process for a significant part of our family.

As an adult visiting Australia, I found myself increasingly reluctant to meet with her. I was put off by her aristocratic airs, missionary zeal, and the way she spoke about Aboriginal people – ungrateful savages who prey on the state’s welfare.

Aliens in their own land

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established in 1972 as an act of defiance against the Australian government’s refusal to recognise Aboriginal land right. Four protesters planted a beach umbrella on the lawn of Parliament House in Canberra with the sign “Aboriginal Embassy”. Despite political discrimination and multiple counts of forced dismantling and removal, it has become an acclaimed site of continued resistance to the policy of assimilation and vital in drawing attention to issues voiced by Aboriginal activists, such as land rights, self-determination and sovereignty.[1]

There have been a number of attacks and suspicious fires at the site. The most devastating arson attack took place in 2003 when 31 years of records were lost. The investigation was neglected by the police, which failed to gather evidence and claimed that CCTV cameras had no footage of the incident. Instead, the fire was used as an argument for another eviction. Darren Bloomfield, who had maintained the Sacred Fire for many years, defended the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, trying to prevent its removal. As a result, he faced several charges in court.[2], [3]

I met Darren in 2013. He is one of the Stolen Generations – kids who were forcibly taken from their families under policies aimed at erasing language, memory and connection to the land. Although shortly after his birth Aboriginal peoples were recognised in the national census as citizens, this did not protect him from being forced to grow up in an environment that denied his identity and left lasting scars.

Darren shared his story with me and allowed me to record it on camera – a gesture of trust for which I remain profoundly grateful.

Here are some more about Darren’s struggle: [1], [2], [3]

Aboriginal teacup

Recently, one of my Aboriginal aunties gave me a teacup decorated with an Aboriginal design. It wasn’t a souvenir shop trinket but a refined, expensive piece. The cup and saucer came in an elegant box, and inside was a card with the name of the person who created the design, along with a short biography. It gave the impression that those behind the product intended to emphasise a sense of support and respect for the Aboriginal peoples and their culture.

Despite efforts behind this gift, it made me strangely angry. I shoved the teacup into a dark corner and tried to forget about it.

But it refused to be forgotten. It lingered at the edge of my mind, like an itch I couldn’t reach. I felt I had abandoned it. So, after some time, I took it out of the darkness and tried to find a place for it in my flat. To no avail, although I tried many positions. At one point, I even considered throwing it away. It doesn’t seem to belong anywhere here.